“First do no harm”, is what one of the earliest documented ethical mandate, the hippocratic oath, teaches us.

Killing (or harming) a patient, such that they are worse off after being seen by a medical practitioner, was the guiding principle that helped managed experimentation in a then new and unknown world.

As we went from magical healing (that had some merits, but not well understood) by tribe elders or healers to a scientific approach supported through technological advancements, experimentation was the key to progress.

A hypothesis was made about something like blood letting for example, but it only worked some of the times but continuous experimentation proved risky and made things worse.

It is that experimental mindset that helped bring in advancements however it was apparent that the principles of treatment had to be managed hand in hand. So experimentation alone wasn’t enough t bring progress, guidelines were necessary.

As I embark on technology ethics at academyEx, it has become something that is weighing heavy on my mind. Technical advancements has been happening at an exponential pace and I do admit it is exciting, but are we “doing no harm”. To quote one of my many astute fellow students “it’s not about moving fast, it’s about moving forward.” Is this happening too fast or are we too slow at responding.

Rapid advancments in artificial intelligence, biometric surveillance, and algorithm-driven social media have made “doing no harm” far trickier than it looked five years ago. Between 2020 and 2025 we have watched deep-fake election ads spread faster than fact-checkers can respond, record data-protection fines levied against Big Tech, and the world’s first comprehensive AI law pass in Europe. Taken together, the lesson is clear: no single actor, government, industry, or academia can keep pace with technology’s ethical risks alone. Only constant, structured collaboration can turn the abstract idea of tech ethics into day-to-day guard-rails.

Why “harm” keeps getting harder to pin down

Viral manipulation and misinformation

- In India’s 2024 national elections AI-generated avatars and audio clips blurred the line between truth and fiction, prompting the country’s former chief election commissioner to warn they could “set the country on fire.” Similar synthetic-media worries surfaced across Europe, where the EU’s Digital Services Act and forthcoming AI Act both single out deepfakes as “systemic risks.”

The data-privacy wake-up call

- Meta’s €1.2 billion GDPR penalty in 2023 remains the largest privacy fine to date and forced firms worldwide to re-audit cross-border data flows. A few months later Meta also agreed to a $725 million settlement over the Cambridge Analytica scandal, reminding regulators that old harms can resurface in new business models.

Algorithmic bias and everyday discrimination

- Investigations into automated hiring tools showed qualified applicants being screened out by opaque filters, underscoring how small design choices can scale into structural inequity.

Government: from back-foot to blueprint

Looking back to 2020, we see government intervention, not only after the fact but upfront to avoid the instance of “harm”.

- April 2021 – EU draft AI rules limit police use of live facial recognition and threaten fines up to 6 % of global turnover. Why it matters : First signal that Brussels would treat certain AI applications as “unacceptable risk.”

- Oct 2023 – US Executive Order on AI forces frontier model developers to share safety test results with Washington. Why it matters : Sets a transparency floor in the world’s largest AI market.

- Nov 2023 – Bletchley Declaration & UK-US safety pact brings 28 countries together around shared testing standards.

- Mar 2024 – EU Parliament approves the AI Act, the first binding, risk-tiered AI framework.

- Apr 2025 – Online Safety Act codes finalised in the UK impose algorithm changes and personal liability for children’s safety.

- Apr 2025 – Ofcom opens first Online Safety Act investigation into a suicide-encouragement forum, signalling early enforcement. Why it these final 4 points matter : Together these moves show regulators shifting from reactive fines to proactive design mandates. A trend that will only accelerate as the EU AI Act phases in from 2025.

Industry: cautiously swapping “move fast” for “test first”

Industry has been seen to adding rigour to their decisions when releasing a new model or new advancement, as a good sign that responsibility and pace can also be profitable.

- Microsoft embedded OpenAI’s ChatGPT technology into “Copilot” only after months of joint red-team testing, betting that rigorous pre-release evaluation would out-compete rivals’ speed.

- Artists’ lawsuits against Stability AI and others over copyrighted training data helped persuade EU lawmakers to add strong transparency clauses to the AI Act.

- Big Tech’s own lobbying push also shows limits: Brussels is now investigating Microsoft’s Bing and Meta’s content-moderation under the Digital Services Act.

Academia & Civil Society: building the evidence base

Peer-reviewed research is framing what “responsible AI” should mean:

- A 2024 Nature review argues that only a globally coordinated authority can keep pace with cross-border AI risks and avoid regulatory fragmentation.

- Studies on trust, governance and healthcare AI published in Nature journals highlight recurring patterns, lack of transparency, unequal data, and unclear accountability. Feeding directly into WHO and OECD guideline work.

Researchers also occupy seats at policy tables: Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute advised the Bletchley Park summit, while academic fellows sit inside NIST’s AI Risk Management working groups in the US.

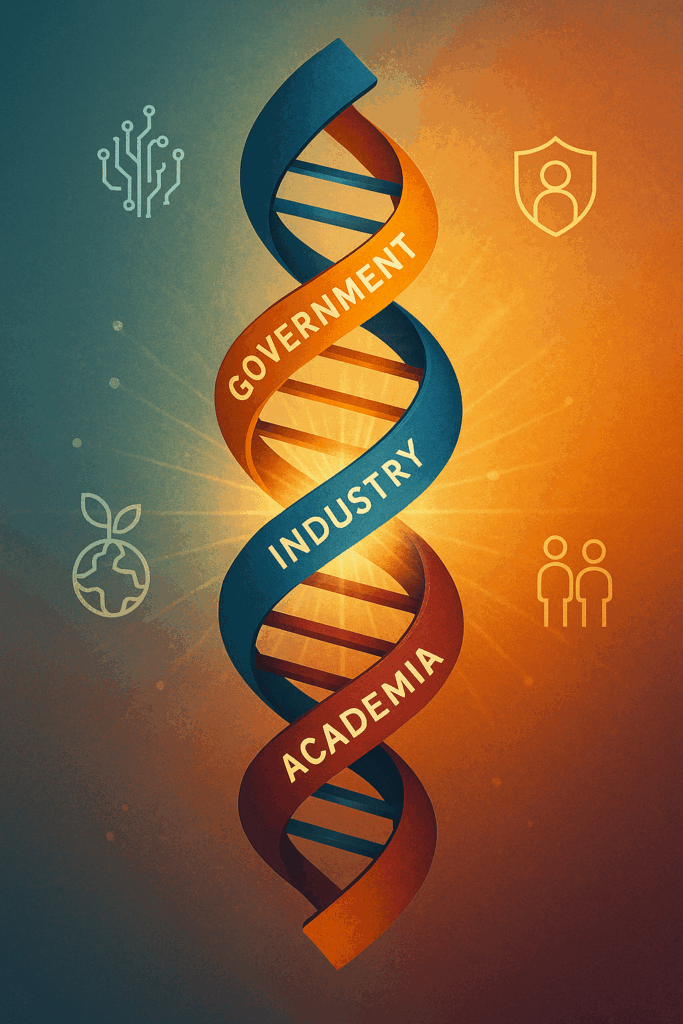

Convergence: why the triple helix matters

Bletchley Park 2023 exemplified the new model: diplomats (government), CEOs (industry) and scholars (academia) co-authored a single declaration on frontier-model testing.

Under the UK-US deal, each country’s AI Safety Institute will share red team protocols and open evaluation sets, work that neither governments nor firms could credibly run alone.

Looking ahead (2025 – 2030)

- Continuous harm assessment : Regulators should require dynamic risk reviews, not one off compliance reports. Open audit sandboxes

- Industry and academia can codevelop reference tests that agencies can adopt without recreating them.

- Global minimum viable principles : The EU AI Act and US EO can seed an eventual treaty, but only if low and middle income nations have a voice.

- Public interest red teams : Fund independent researchers to stress-test models, mirroring the security community’s role in cryptography.

- Ethics by design education : Embed multidisciplinary ethics modules in computer science and Masters programmes to normalise cross sector thinking.

If the past five years have taught us anything, it is that ethical guardrails arrive most quickly and stick most firmly, when government sets an enforceable floor, industry treats safety as a competitive advantage, and academics keep both honest with evidence. Keeping that trisector conversation alive is now the central task of tech ethics.

Still not enough

As I conclude this investigative research, I would be remiss to not identify areas that I have not dug into yet. the existing inequities that exist globally with regards to technological advancements.

Technology can magnify existing inequities for groups that already sit at society’s margins.

- First, the explosion of #ADHD, tagged videos on TikTok, more than 20 billion views has spread welcome awareness, but doctors told the BBC it is also driving a wave of inaccurate self-diagnosis that leaves many neurodivergent people without proper care or protection from exploitative “quick-fix” services

- Second, during Australia’s 2023 referendum on creating an Indigenous “Voice to Parliament,” researchers traced an “ecosystem of disinformation” to social media algorithms that amplified racist memes and manipulated videos; Aboriginal health advocates warned the resulting online hate was pushing First Nations suicide prevention hotlines to record demand .

Together these cases show why ethical review must extend beyond technical safety to ask who is being targeted, who is being left out, and how algorithmic design choices can translate into very real harms for people with ADHD, Māori, Aboriginal and countless others whose voices are too easily drowned out.

I hope you enjoyed this research and if you have any insight or opinion on what needs to be done to manage the inequity gaps while still managing technological advancements ethically and at pace please reach out. It is something I am embarking on discovering as my “next piece of work”

Sources

- BBC News. (2023, October 30). TikTok ADHD videos may be driving people to self-diagnose, say doctors. https://www.bbc.com/news/health-67229879

- BBC News. (2023, October 17). TikTok and the Voice: The misinformation swirling around Australia’s referendum. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-67101571

- BBC News. (2023, May 22). Meta fined €1.2bn by EU over US data transfers. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-65672179

- BBC News. (2023, December 18). EU agrees landmark rules on artificial intelligence. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-67657424

- BBC News. (2023, November 1). AI safety: World leaders sign Bletchley Declaration. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-67285943

- BBC News. (2023, October 31). US issues landmark AI safety order. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-67254696

- BBC News. (2024, April 12). UK watchdog investigates social media site under Online Safety Act. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-68769563

- BBC News. (2023, December 4). Australia’s Meta and Google showdown over misinformation laws. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-67681129

- European Commission. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Act. https://artificial-intelligence-act.eu

- European Commission. (2022). Digital Services Act (DSA). https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

- White House. (2023, October 30). Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/10/30/executive-order-on-the-safe-secure-and-trustworthy-development-and-use-of-artificial-intelligence/

- Bletchley Park Declaration. (2023). Bletchley Declaration on AI Safety. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/ai-safety-summit-2023-bletchley-declaration

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). (2023). AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0). https://www.nist.gov/itl/ai-risk-management-framework

- OECD. (2019). OECD Principles on Artificial Intelligence. https://oecd.ai/en/ai-principles

- Leslie, D. (2023). Understanding the gap: A review of AI ethical principles and their implications. Nature Machine Intelligence, 5(4), 289–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00626-5

- Floridi, L., & Cowls, J. (2019). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1